In this post I will improve the performance of an algorithm that converts RGB888 images to RGB565. It is divided into different sections:

First, I will give a brief introduction on RGB888 RGB565 and converting between the two, and present a scalar algorithm that achieves this task.

Next, I will use SIMD Neon instructions to attempt to manually ‘optimize’ this algorithm. I will also introduce an optimized version that uses special SIMD instructions and a slightly different approach to improve the theoretical throughput of the algorithm even further.

Finally, I will present the benchmarking results and compare different versions against each other.

The post will end with a conclusion and a couple of final words.

Any benchmarks are conducted on a MacBook with an M3 Pro CPU with 10 cores, though the code is single threaded. Code is compiled in C23 mode with -O3 (unless stated otherwise).

Benchmarks are ran on 200x200 RGB888 images since I had those on hand from a different project. Note that the performance difference will be marginal in absolute numbers. Partially because of the performant underlying hardware and partially because of the image size of course.

Any performance improvements are to be seen relatively to what they are compared to, since these conclusions similarly apply to bigger problems where the timescale might not be in the $\mu$s range.

Introduction

What is SIMD?

‘Single Instruction Multiple Data’ (SIMD) can be used to improve the performance of algorithms that require the same transformations on a wide range of data. This is achieved by increasing data throughput for every instruction (operating on up to 512 bit ‘vectors’ instead of traditional 64 bit registers).

Transforming RGB888 to RGB565

Transforming 24 bit RGB (8 bits per color channel) into 16 bit RGB effectively means cramming the information contained in 8 bits into 5 or 6 bits and then putting these pixels into a 16 bit value.

There are different approaches to achieve this. The first and most simple one is to just truncate the last 2 or 3 bits.

Taking 3 bit truncation as an example, values would be mapped as follows:

0-7 -> 0

8-15 -> 1

16-23 -> 2

…

When truncating 2 bits 0-3 are mapped to 0, 4-7 that are mapped to 1, and so on.

This is efficient, especially when using SIMD instructions and even has an example in the ‘Coding for Neon’ guide 1. However, it introduces a bias. It would be better if there was a way to map 4-11 to 1 instead of 8-15, which would be similar ‘rounding’.

This is possible due to offsets, so before shifting by 3 (dividing by 8), half of that is added (+4). This results in:

0-3 -> 0

4-11 -> 1

12-17 -> 2

…

A scalar version of this algorithm could look like this:

1void rgb888_to_rgb565_scalar(Image *src, Image *dst) {

2

3 for (int i = 0; i < src->img_width * src->img_height; i++) {

4 // retrieve RGB 888 values

5 uint8_t r = src->buffer[i * 3 + 0];

6 uint8_t g = src->buffer[i * 3 + 1];

7 uint8_t b = src->buffer[i * 3 + 2];

8

9 // add half the lost precision before truncating

10 uint16_t r5 = (r + 4) >> 3; // +4 is half of 8 (2^3)

11 uint16_t g6 = (g + 2) >> 2; // +2 is half of 4 (2^2)

12 uint16_t b5 = (b + 4) >> 3; // +4 is half of 8 (2^3)

13

14 // clamp to prevent overflow

15 if (r5 > 31)

16 r5 = 31;

17 if (g6 > 63)

18 g6 = 63;

19 if (b5 > 31)

20 b5 = 31;

21

22 // packing 16 bit value

23 uint16_t value = (uint16_t)((r5 << 11) | (g6 << 5) | b5);

24

25 // save RGB 565 values

26 ((uint16_t *)dst->buffer)[i] = value;

27 }

28}

Vectorizing

SIMD on Arm is implemented by the Neon architecture extension. The register width is 128 bits, which is pretty small when compared to different SIMD extensions on x86, such as 512 bits on AVX 512 or 256 bits on AVX2. So the maximum number of values that would fit in a Neon register are 16 8 bit values.

I have used the intrinsics provided by the neon.h header file, as opposed to inline assembly.

The instructions will be the same, but the code is much more readable and easier to write.

The corresponding type provided by the Neon header file for our 16 8 bit values data type would be uint8x16_t.

One more type that will be very useful is uint8x16x3_t, representing 3 uint8x16_ts, which is perfect for dealing

with color channels.

Naive Approach

Vectorizing this algorithm is very easy, since pixels are stored consecutively in a RGBRGBRGB pattern.

However, there is one problem: The scalar algorithm does any arithmetic operations on 16 bit values, due to the chance of overflows. So while it is possible to load 16 pixels using one instruction and packing 16 color values into one register, the actual processing has to be done one 16-bit integers, which limits the number of color values per register to 8.

So that means one of two things for the vectorized version:

- Only load 3x8 values, since that is the max numbers that can be processed with one instruction. I will refer to this approach as ‘8P’ moving forward.

- Load 3x16 values, but separate the color values into 2 registers per channel before doing arithmetic operations. I will refer to this approach as ‘16P’ in the future.

The number of arithmetic instruction required to process the data is the same for both approaches.

The second approach (16P) will process 16 pixels per iteration, but requires twice the add, shift and or instructions.

However, processing 16 pixels per iteration reduces the required load instructions by half, and the same

actually applies to stores as we will see later.

Though this comes at the cost of a higher register usage.

This is also reflected in the generated assembly.

Particularly interesting are the parts inside the for-loop.

The first 2 instructions (locations 100001e58 & 100001e5c in the 8P implementation)

load the source and compute the offset to load the pixels to be processed into the correct registers.

The algorithm really starts ld3.8b { v4, v5, v6 }, [x11] at 100001e60 loading the pixels into SIMD registers.

16P uses the ld3.16b { v4, v5, v6 }, [x11] instruction instead (from location 100001f30)

As you can see they are almost identical, the only difference is in the operand suffix (16b vs 8b).

The number indicates the number of values that are loaded, and the letter describes the data type.

In this case 16 bytes and 8 bytes respectively2.

The rest is exactly the same except that 16P executes every arithmetic instruction

twice (once on the upper and once on the lower half of course) and uses more registers.

Below is a brief explanation of the entire generated assembly for the loop body. The full assembly can be found in the Appendix.

1100001e58: f940000b ldr x11, [x0] ; load source buffer

2100001e5c: 8b08016b add x11, x11, x8 ; compute current location offset

3100001e60: 0c404164 ld3.8b { v4, v5, v6 }, [x11] ; load pixels

4100001e64: 2e241007 uaddw.8h v7, v0, v4 ; add 4 to red

5100001e68: 2e251030 uaddw.8h v16, v1, v5 ; add 2 to green

6100001e6c: 6f1d04e7 ushr.8h v7, v7, #0x3 ; shift red

7100001e70: 6f1e0610 ushr.8h v16, v16, #0x2 ; shift green

8100001e74: 2e261004 uaddw.8h v4, v0, v6 ; add 4 to blue

9100001e78: 6f1d0484 ushr.8h v4, v4, #0x3 ; shift blue

10100001e7c: 6e626ce5 umin.8h v5, v7, v2 ; clamp red

11100001e80: 6e636e06 umin.8h v6, v16, v3 ; clamp green

12100001e84: 4f1b54a5 shl.8h v5, v5, #0xb ; shift red to its location in the 16 bit buffer

13100001e88: 4f1554c6 shl.8h v6, v6, #0x5 ; shift green to its location in the 16 bit buffer

14100001e8c: 6e626c84 umin.8h v4, v4, v2 ; clamp blue

15100001e90: 4ea51cc5 orr.16b v5, v6, v5 ; or red and green together

16100001e94: 4ea41ca4 orr.16b v4, v5, v4 ; or blue with red & green

17100001e98: f940002b ldr x11, [x1] ; load destination base pointer

18100001e9c: 3ca96964 str q4, [x11, x9] ; write result back to buffer

19100001ea0: 9100214a add x10, x10, #0x8 ; i += 8

20100001ea4: a941300b ldp x11, x12, [x0, #0x10] ; load loop bound values

21100001ea8: 9b0b7d8b mul x11, x12, x11 ; compute total/limit

22100001eac: 91004129 add x9, x9, #0x10 ; advance output pointer (16 bytes)

23100001eb0: 91006108 add x8, x8, #0x18 ; advance input pointer (24 bytes)

24100001eb4: eb0a017f cmp x11, x10 ; check for condition

25100001eb8: 54fffd08 b.hi 0x100001914 <_rgb888_to_rgb565_neon_8vals+0x54> ; branch based on comparison result

This totals 25 instructions from load to branch, resulting in 3.125 instructions per pixel.

The same routine, when processing 16 pixels per iteration (from location 100001f28 to 100001fc8,

see Appendix), takes 41 instructions, resulting in 2.5625 instructions per pixel.

So all else being equal it is expected that 16P is a little faster, at least assuming there is no cost associated with the extra register usage. Note that that might not always be the case, especially with high memory pressure. However, the benchmarks are conducted with enough free RAM and low memory pressure to reduce influences by outside, non-related causes.

Optimized Algorithm

However, 16P has one fundamental flaw:

It does not truly increase the throughput by 16x.

While 8P actually processed 8 pixels with a similar amount of instructions, 16P only loads and stores 16 pixels at once. For processing, the pixels are split into two 8 value registers, since the processing is fundamentally done on 16 bit values, so it is technically not possible to do arithmetic operations on 16 values at once, due the register sizes of 128 bits.

To actually process 16 pixels, at least through most of the iteration, the algorithm has to be slightly changed, so that more arithmetic operations can be done on 8 bit values. And there is a way, that allows for processing 16 pixels for most of the algorithm, only splitting and moving them into registers holding 16bit values when combining the 3 color channels to RGB565.

Fundamentally, instead of clamping the values after adding and shifting, an overflow detection could be implemented that then sets the value to 255 if it overflowed. This will result to the correct maximum of 31 & 64 respectively after shifting.

Scalar pseudocode would look like this:

1void rgb888_to_rgb565_neon(Image *src, Image *dst) {

2 for (int i = 0; i < src->img_width * src->img_height; i++) {

3

4 uint8_t r = src->buffer[i * 3 + 0];

5 // same for green & blue just like before

6

7 uint8_t r5 = r + 4;

8 // +2 for green & +4 for blue, just like before

9

10 if (r5 < r)

11 r5 = 255;

12 // same for green & blue

13

14 r5 = r5 >> 3;

15 // shift green & blue like before

16

17 uint16_t value = (uint16_t)((r5 << 11) | (g6 << 5) | b5);

18

19 ((uint16_t *)dst->buffer)[i] = value;

20 }

21}

A naive vectorization of the comparison operation of this version would be more complicated though.

The clamping in the original algorithm is essentially just a min between the

actual value and the max value.

When using Neon the vminq_u16 intrinsic can be used for this.

Reimplementing logic like that in Neon requires the comparison using vcgtq_u8, creating a mask,

followed by vbslq_u8, which uses the mask to either set the current value or 255.

The full implementation of this implementation can be found in the Appendix.

However, there is a way to avoid the comparison and masking through the use of ‘saturating arithmetic’.

A ‘saturation add’ will perform a pairwise addition as usual, but it will cap the result at the maximum value

(255 for 8 bit values).

Which is exactly what is needed here. The intrinsic for this operation is vqaddq_u8.

This implementation can also be found in the Appendix.

Using ‘saturation math’ is not only simpler to implement but also expected to provide an even

more substantial performance improvement, since it reduces the number of required instructions compared to the masking approach.

Throughout this post, I will use ‘Optimized Algorithm’ (or ‘OA’) to refer to algorithm as a whole. If it is necessary to distinguish between both implementations, ‘OA’ will refer to the one using masks and ‘SA’ or ‘Saturation Add’ will refer to the one using the ‘saturation add’ operation.

Benchmarks

First I will give brief introduction on the benchmarking & data collection settings and environment. This is followed by a concise analysis of the collected data. Finally, I will go over the different results comparing different implementations and finish this section with a brief subsection about limitations.

The purpose of these benchmarks are to answer the following questions:

- When vectorizing the original algorithm, is the extra register usage of processing 16 pixels per iteration better than processing 8 pixels per iteration?

- Can the compiler automatically vectorize the algorithm? How would the compiler generated version compare to the hand vectorized version?

- How does the improved algorithm compare against the compiler generated version?

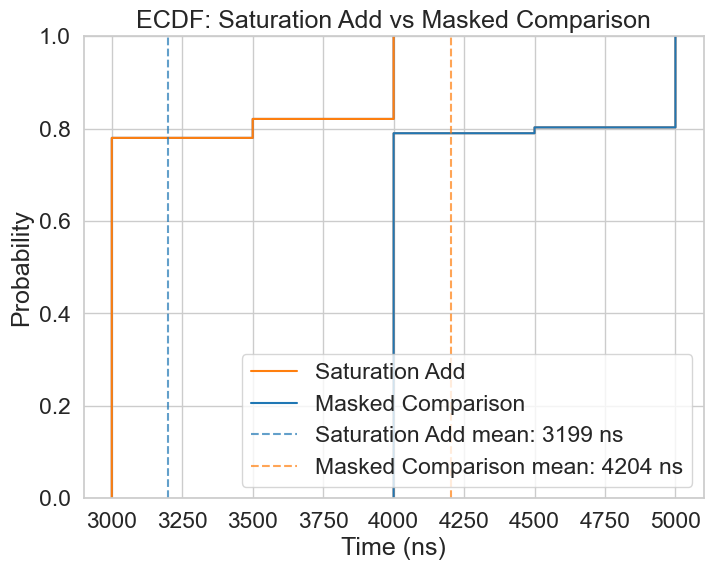

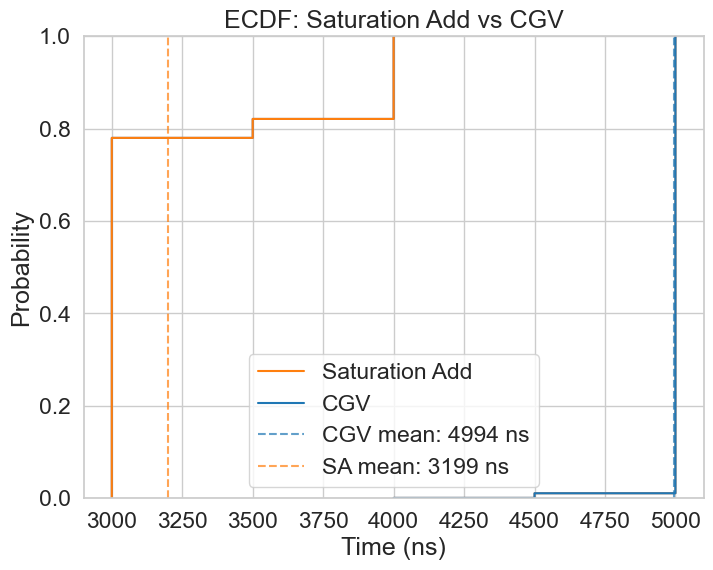

- What is the difference does the use of the ‘saturation add’ make?

- What is the baseline speed (scalar) and how do the different versions compare against baseline but also against each other?

Benchmark settings

The parameters under which the benchmarks were ran are as follows:

- Benchmarks are executed on 2682 RGB888 images with 200x200 pixels.

- The benchmark runs every function on every image.

- There are always 5 warm-up runs before the timed runs.

- There are 20 timed runs and the median is selected as the particular result for that function & image combination.

- Output buffers are reused but set to 0 after every run.

- Every image runs in its own process to avoid crashes in case of invalid inputs, but they are running sequentially.

- I am running the benchmarks on a MacBook M3 Pro (no power saving mode).

setpriorityis used to increase the processes priority and thereby reduce interference by other processes.

Data Analysis

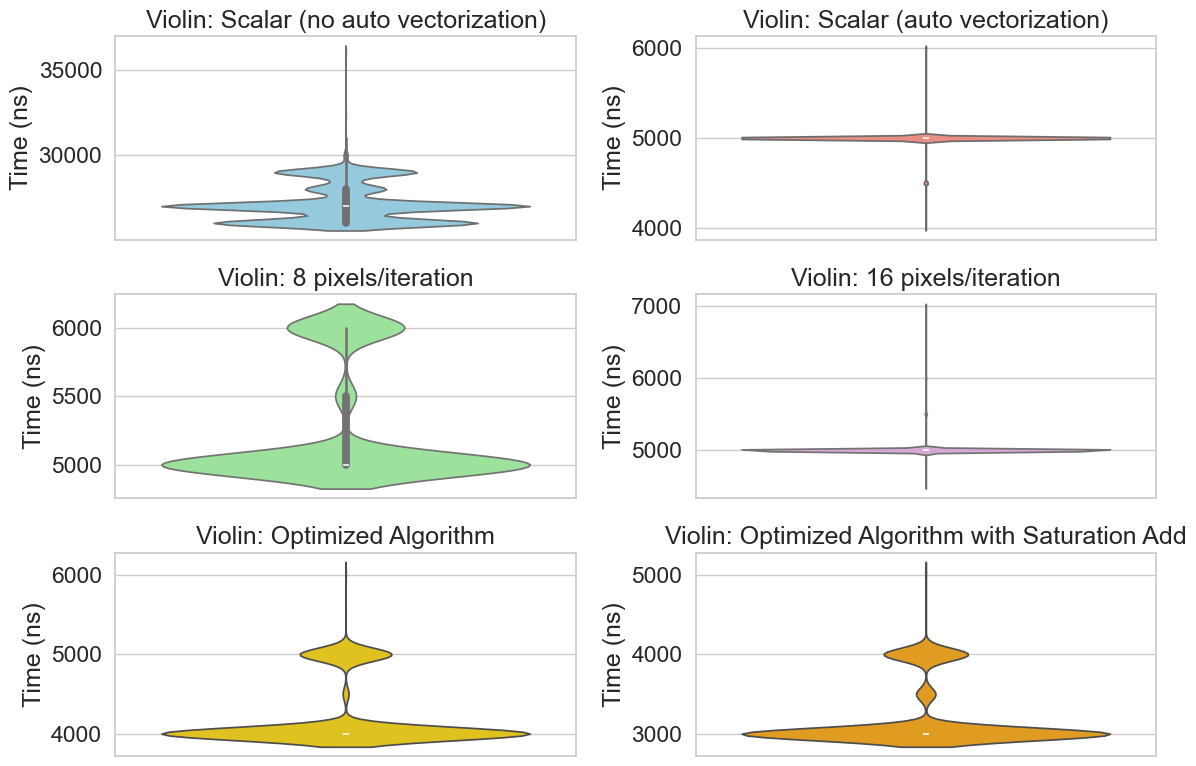

Figure 1.1 shows the collected data.

There are some significant outliers, due to a variety of possibilities.

On macOS it’s unfortunately not possible to pin processes to a specific CPU, so those could be due to context switches.

They could also possibly be due to interrupts from the operating system.

Unfortunately it appears that it is not possible to set scheduling settings such as SCHED_FIFO on Linux either.

I have tried to minimize outside influences and reduce memory pressure by closing unimportant programs such as browsers or any other user programs that would be running on my machine. But I don’t have a specific benchmarking machine set up just for benchmarks, so they were ran on my personal laptop, so there still are likely suboptimal conditions influencing the benchmark.

To try to get as reliable results as possible, I have set the priority/niceness using setpriority (which obsoletes nice3).

I also set the QoS settings to the highest priority to try and keep the benchmark on a P-Core4.

1// set priority

2if (setpriority(PRIO_PROCESS, 0, -20) == -1) {

3 perror("setpriority failed - try running as root");

4 return 1;

5}

6

7// Set QoS to user-interactive to encourage P-core scheduling

8if (pthread_set_qos_class_self_np(QOS_CLASS_USER_INTERACTIVE, 0) != 0) {

9 perror("pthread_set_qos_class_self_np failed");

10 return 1;

11}

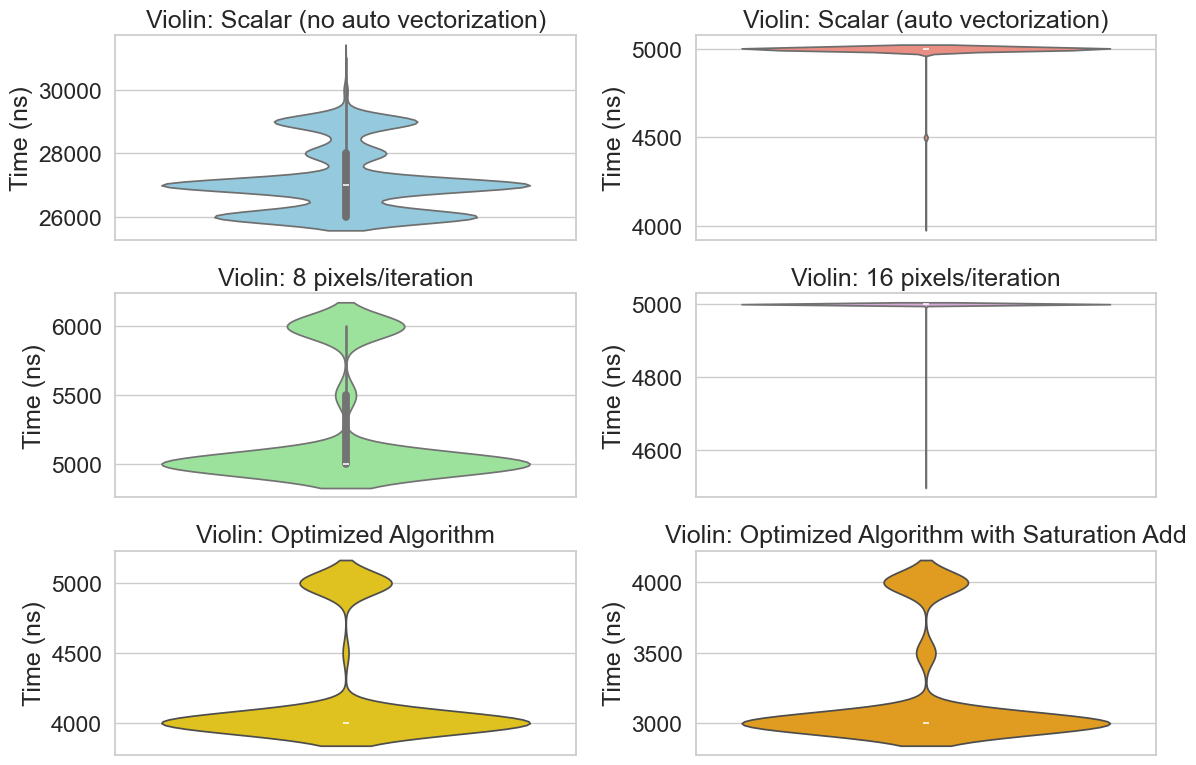

Since I didn’t want to distort the data, I took a reliable but conservative approach to removing outliers. For each function, I replaced any values above the 80^(th) percentile or below the 20^(th) percentile with the median. The corrected distributions are displayed in Figure 1.2

Baseline

First it is important to establish a baseline that any optimization is compared against.

For this a truly scalar implementation is used.

To achieve this, -O3 optimizations were enabled during compilation (same as every other function).

However, to make sure the compiler does not vectorize the algorithm, 2 pragmas were used:

#pragma clang loop vectorize(disable) and #pragma clang loop interleave(disable).

Mean execution time for this configuration is 27031ns.

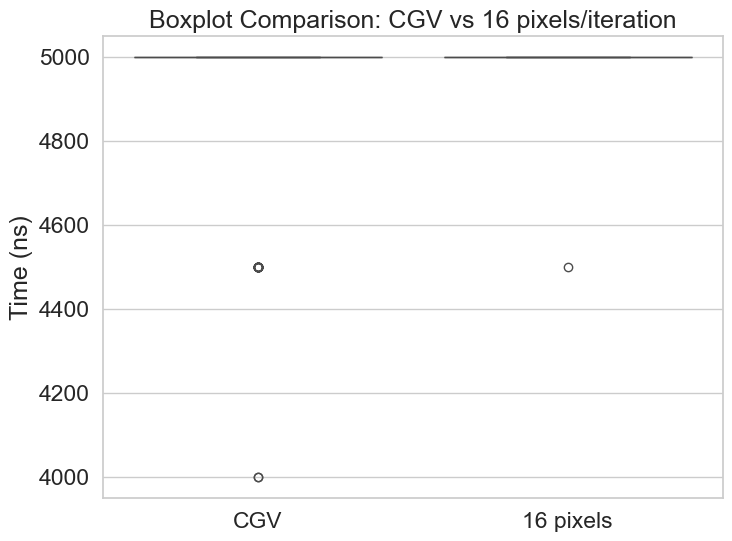

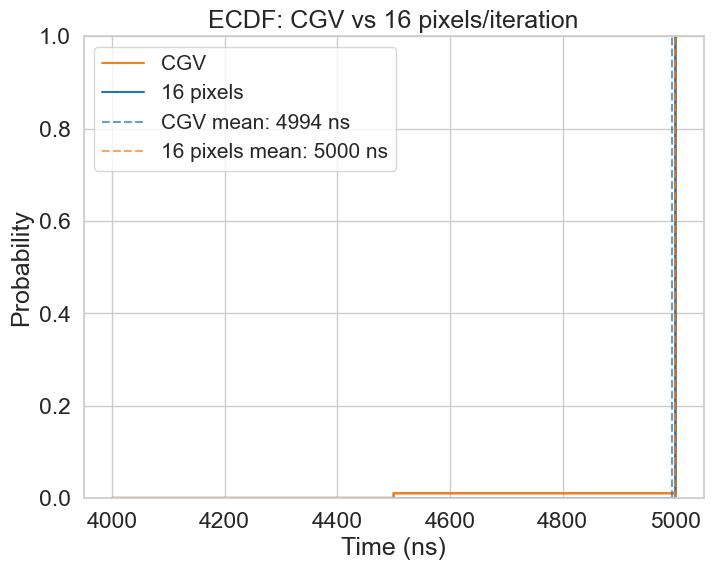

8 vs 16 pixels per iteration

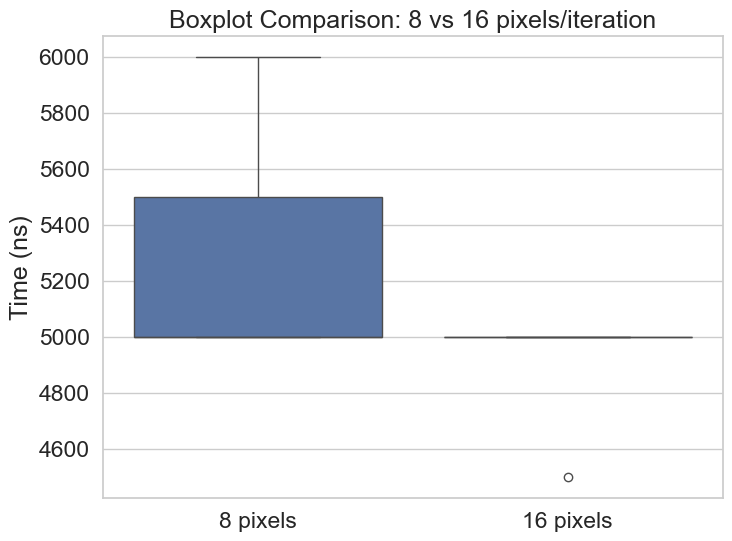

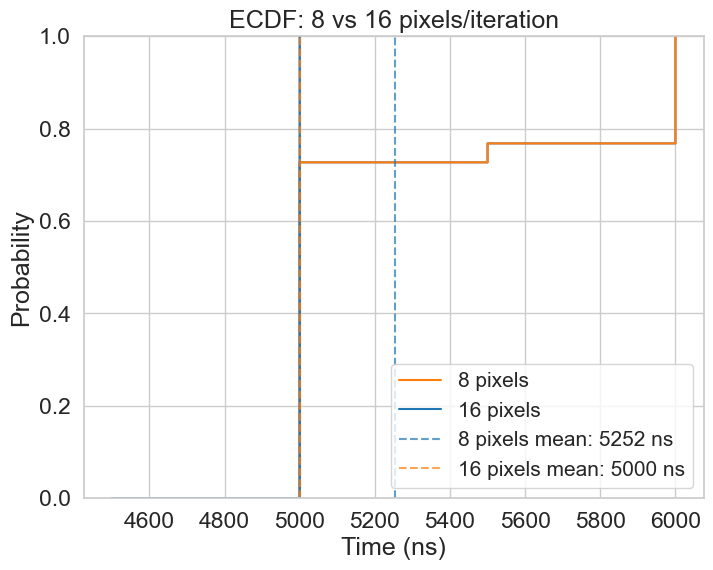

While both approaches achieve an equal median performance, processing 16 pixels per iteration shows better consistency, and a slightly higher mean performance, as displayed in the ECDF. The Boxplot also suggests that the worst case execution time of 16P appears to be an outlier, which could be due to other factors such as context switches or CPU frequency scaling, as the boxplot is very flat at a consistent 5000ns. 8P, on the other hand shows equal performance to 16P on the lower and medium quatiles, but starts to diverge at the higher quartiles.

I’ve determined that 16P outperforms 8P slightly, given that 8P’s performance is more variable and has a marginally, but significant, higher mean.

So to answer the question:

- When vectorizing the original algorithm, is the extra register usage of processing 16 pixels per iteration better than processing 8 pixels per iteration?

Yes, given the benchmarking parameters, 16P outperforms 8P. Though not by much.

Auto Vectorization

In this section I will look into the optimizations that the compiler made to scalar algorithm, to answer the questions:

- Can the compiler automatically vectorize the scalar implementation?

- How does it perform compared to other implementations?

Analysis

The full assembly can be found in the Appendix, but I will give a brief overview here:

The compiler actually generated 3 different paths:

- A truly scalar version (similar to the one would be generated if you disable the vectorization optimizations).

- A version that processes 8 pixels per iteration (similar to what I wrote by hand).

- A version that processes 16 pixels per iteration (similar to what I wrote by hand).

So yes, the compiler can automatically vectorize this algorithm/implementation.

I will refer to this as ‘CGV’ (‘Compiler Generated Version’) moving forward.

I did a full deep dive on the difference between the assembly generated from the 16P and the CGV in this post here, going over the generated assembly line by line with explanations as to why the compiler might have generated those particular instructions. But the main difference came from the way values were written back to memory at the end of each iteration.

In the CGV, this is done by a single instruction:

110000171c: ac8115a4 stp q4, q5, [x13], #0x20

The stp instruction takes two SIMD vectors and stores them to a specific address plus a given offset,

basically vectorizing the ‘store’.

The store sequence for the version that I vectorized were a little more complex and less efficient.

Below you can see the 5 instructions, that the compiler generated. They load the store address from memory twice and then individually store the data to the respective offset:

- ‘$2 \cdot i$’, as

icounts number of pixels, each pixel being 2 bytes, and - ‘$2 \cdot i + 16$’, for the second set of 8 pixels, again, each pixel being 2 bytes.

1100001f98: f940002b ldr x11, [x1] ; load store address (dst->buffer) from memory

2; ... remaining scheduled SIMD instruction

3100001fa0: 3ca96964 str q4, [x11, x9] ; store q4 to base + (2 * i)

4100001fa4: f940002b ldr x11, [x1] ; load store address (dst->buffer) from memory

5100001fa8: 8b09016b add x11, x11, x9 ; x11 = 2 * i

6100001fac: 3d800565 str q5, [x11, #0x10] ; store q5 to (2 * i) + 16

Results

As one can see in the benchmark results of the CGV and 16P versions below, they perform almost the same. The difference is actually slightly larger if the benchmarks are ran with a ’niceness’ of 0, then the CGV slightly, but measurably outperforms 16P. However, there is no real difference with a ’niceness’ of -20.

Adjusting the code, so the compiler also generates a stp instruction for my manually

vectorized version also closes the gap with a ’niceness’ of 0.

So in the end, the compiler generated the same SIMD instructions, but it could generate slightly better assembly around that. Again, in a different post I use this example to try and figure out why that is.

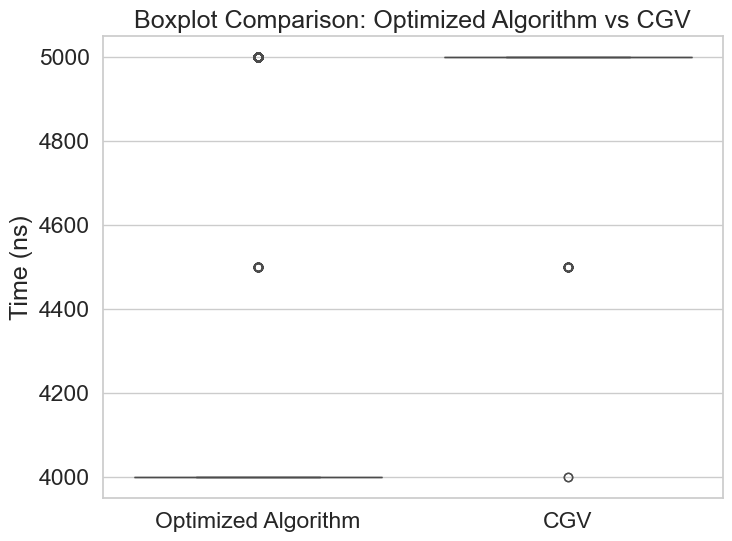

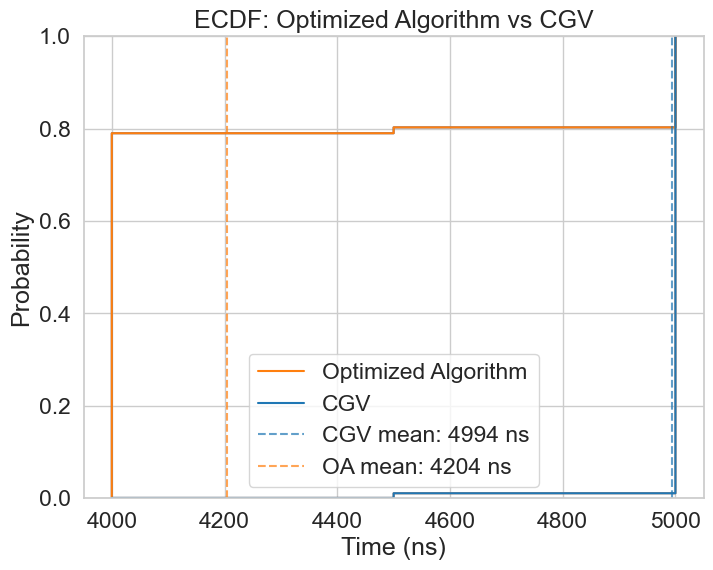

Optimized Algorithm

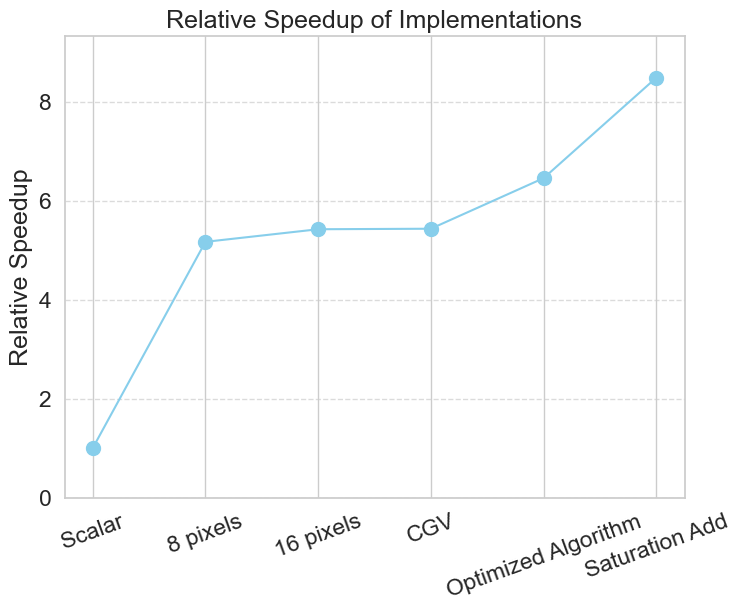

Since the CGV and 16P versions are essentially equal, it is expected that the Optimized Algorithm outperforms them both, since it essentially doubles throughput for at least part of the arithmetic. The figure below displays this performance improvement of 6.46 times higher compared to scalar baseline (as opposed to 5.44x from CGV).

Saturation Add

The usage of the saturation add widens this difference even further, resulting in an 8.49x improvement compared to baseline. The corresponding ECDF illustrates this very clearly, outperforming even the original OA by 1/4.

Summary

An 8.5x speedup to a truly scalar version can be achieved by using vectorization. However, modern compilers are able to achieve very good results as well, and the only way to really beat it (in this instance) was to make bigger algorithmic changes, that a compiler would not do. It is not clear how well this applies to algorithms that are less trivial to optimize though.

There also is a stark drop-off in performance improvement when moving from processing 8 pixels per iteration to 16, until the Optimized Algorithm (with ‘saturation add’) caused a significant jump by enabling the higher throughput, with a similar amount of operations. A curve about the speedup trend can be found below the table.

| Implementation | Mean (ns) | 90th Percentile (ns) | Relative Speedup |

|---|---|---|---|

| scalar (no auto vectorization) | 27149.33 | 29000.0 | 1.00 |

| CGV | 4994.22 | 5000.0 | 5.44 |

| 8 pixels | 5252.42 | 6000.0 | 5.17 |

| 16 pixels | 4999.81 | 5000.0 | 5.42 |

| Optimized Algorithm | 4203.58 | 5000.0 | 6.46 |

| OA with Saturation Add | 3199.48 | 4000.0 | 8.49 |

Limitations

I wanted to use pthread_set_qos_class_self_np as well but macOS does not allow this when forking processes.

It can be done when using posix_spawn instead, might do that in the future to see if it makes a difference.

After all, setpriority makes a huge difference, not only on the performance numbers themselves, but also on the consistency,

and thereby the distributions as a whole.

I had collected data without setting the priority/nice value, and those results do look different.

While I have reduced the amount of programs running in the background to keep memory pressure low, there is no way completely control the caches or different processes. MacOS also doesn’t have any real time or priority scheduling, or CPU pinning, so there will be some influence due to interrupts/context switches.

It might be interesting running the same benchmarks on a dedicated benchmarking machine with more control over the operating system. I might try this in the future using a Raspberry Pi.

Conclusions

1. Modern Compilers are pretty good

Modern compilers are very capable at vectorizing code themselves. At least for easily optimizable problems. Manual ‘optimizations’ might actually keep the compiler from some improvements in other areas, so it might not only be not worth it, but also hurting.

However, it might be worth it when vectorization allows you to make structural improvements to the algorithm, that a compiler would not be able to do (as in the case of the ‘Optimized Algorithm’). But ‘dumb vectorization’ is probably better left to the compiler. And if not it should be accompanied by incremental benchmarks.

2. Images are rather small

The performance differences are of course in the scale of microseconds, so the differences/improvements will likely go unnoticed. This is partially due to the relatively low number of iterations, due to the limited image size: $$ \frac{200 \cdot 200 \text{ pixels}}{16 \text{ pixels/iteration}} = \frac{40 000 \text{ pixels}}{16 \text{ pixels/iteration}} = 2 500 \text{ iterations}$$

For bigger image sizes or applications that process more data in general (such as processing point clouds), the difference can be noticeable.

3. It’s really important to know the platform specific instructions/intrinsics

The implementation process of the optimized algorithm shows how important it is to know the instructions of the platform the algorithm is implemented for. Without using the saturation additions for example, the optimized version would only be ~19% faster than the compiler generated version of the original algorithm. As opposed to the ~56% speedup one would gain using the more optimal instructions.

4. Real world vs theoretical performance

The theoretical performance gain for an 8P like implementation would be 8x relative to baseline. The actual result is ~5x, which is significant, but not close to the theoretical limit. The theoretical performance gain overall could be considered to be 16x, since 16 8bit values fit into one 128 bit register. However, naive optimizations (by the compiler or by hand) does not necessarily bring you there. Furthermore, I was not able to achieve this level of throughput throughout the whole loop body.

So in reality, there is a:

- 16x speedup for the loads

- 16x speedup for the first addition incl. saturation

- 16x speedup for the shift right

After that, green and red are split into upper and lower halfs, adding some penalty there, followed by:

- 8x speedup in red and green shift

- 8x speedup

oring the values together

Finally, if a stp instruction is emitted by the compiler,

then there is a 16x speedup in the store. Else it’s 8x.

It is hard to put an exact number on what the expected speedup should be, however assuming the 16x and 8x parts make up 50% each, then a $\frac{8 + 16}{2} = 12x$ theoretical improvement could be expected. Though that might not necessarily be accurate since memory access tends to be particularly slow.

Either way, the final performance peak was ~8.5x, which shows, that there can be a significant gap between expected/theoretical and actual performance.

While there may be additional improvements possible through smarter register management, 8.5x is as good as I can get it at this time. I might revisit this in the future to see if I can figure out a way to do better.

Appendix

Processing 8 pixels per iteration (8P)

1void rgb888_to_rgb565_neon_8vals(Image *src, Image *dst) {

2

3 const uint16x8_t v_4 = vdupq_n_u16(4);

4 const uint16x8_t v_2 = vdupq_n_u16(2);

5 const uint16x8_t v_31 = vdupq_n_u16(31);

6 const uint16x8_t v_63 = vdupq_n_u16(63);

7

8 uint8x8x3_t v_rgb888;

9 uint16x8_t v_rgb565;

10

11 for (int i = 0; i < src->img_width * src->img_height; i += 8) {

12

13 v_rgb888 = vld3_u8(src->buffer + (i * 3));

14

15 uint16x8_t v_r = vmovl_u8(v_rgb888.val[0]);

16 uint16x8_t v_g = vmovl_u8(v_rgb888.val[1]);

17 uint16x8_t v_b = vmovl_u8(v_rgb888.val[2]);

18

19 v_r = vaddq_u16(v_r, v_4);

20 v_g = vaddq_u16(v_g, v_2);

21 v_b = vaddq_u16(v_b, v_4);

22

23 v_r = vshrq_n_u16(v_r, 3);

24 v_g = vshrq_n_u16(v_g, 2);

25 v_b = vshrq_n_u16(v_b, 3);

26

27 v_r = vminq_u16(v_r, v_31);

28 v_g = vminq_u16(v_g, v_63);

29 v_b = vminq_u16(v_b, v_31);

30

31 v_r = vshlq_n_u16(v_r, 11);

32 v_g = vshlq_n_u16(v_g, 5);

33

34 v_rgb565 = vorrq_u16(v_r, v_g);

35 v_rgb565 = vorrq_u16(v_rgb565, v_b);

36

37 vst1q_u16((uint16_t *)dst->buffer + i, v_rgb565);

38 }

39}

10000000100001e04 <_rgb888_to_rgb565_neon_8vals>:

2100001e04: a9bf7bfd stp x29, x30, [sp, #-0x10]!

3100001e08: 910003fd mov x29, sp

4100001e0c: f9400808 ldr x8, [x0, #0x10]

5100001e10: f103211f cmp x8, #0xc8

6100001e14: 54000581 b.ne 0x100001ec4 <_rgb888_to_rgb565_neon_8vals+0xc0>

7100001e18: f9400c08 ldr x8, [x0, #0x18]

8100001e1c: f103211f cmp x8, #0xc8

9100001e20: 54000541 b.ne 0x100001ec8 <_rgb888_to_rgb565_neon_8vals+0xc4>

10100001e24: f9400828 ldr x8, [x1, #0x10]

11100001e28: f103211f cmp x8, #0xc8

12100001e2c: 54000501 b.ne 0x100001ecc <_rgb888_to_rgb565_neon_8vals+0xc8>

13100001e30: f9400c28 ldr x8, [x1, #0x18]

14100001e34: f103211f cmp x8, #0xc8

15100001e38: 540004c1 b.ne 0x100001ed0 <_rgb888_to_rgb565_neon_8vals+0xcc>

16100001e3c: d2800008 mov x8, #0x0 ; =0

17100001e40: d2800009 mov x9, #0x0 ; =0

18100001e44: d280000a mov x10, #0x0 ; =0

19100001e48: 4f008480 movi.8h v0, #0x4

20100001e4c: 4f008441 movi.8h v1, #0x2

21100001e50: 4f0087e2 movi.8h v2, #0x1f

22100001e54: 4f0187e3 movi.8h v3, #0x3f

23100001e58: f940000b ldr x11, [x0]

24100001e5c: 8b08016b add x11, x11, x8

25100001e60: 0c404164 ld3.8b { v4, v5, v6 }, [x11]

26100001e64: 2e241007 uaddw.8h v7, v0, v4

27100001e68: 2e251030 uaddw.8h v16, v1, v5

28100001e6c: 6f1d04e7 ushr.8h v7, v7, #0x3

29100001e70: 6f1e0610 ushr.8h v16, v16, #0x2

30100001e74: 2e261004 uaddw.8h v4, v0, v6

31100001e78: 6f1d0484 ushr.8h v4, v4, #0x3

32100001e7c: 6e626ce5 umin.8h v5, v7, v2

33100001e80: 6e636e06 umin.8h v6, v16, v3

34100001e84: 4f1b54a5 shl.8h v5, v5, #0xb

35100001e88: 4f1554c6 shl.8h v6, v6, #0x5

36100001e8c: 6e626c84 umin.8h v4, v4, v2

37100001e90: 4ea51cc5 orr.16b v5, v6, v5

38100001e94: 4ea41ca4 orr.16b v4, v5, v4

39100001e98: f940002b ldr x11, [x1]

40100001e9c: 3ca96964 str q4, [x11, x9]

41100001ea0: 9100214a add x10, x10, #0x8

42100001ea4: a941300b ldp x11, x12, [x0, #0x10]

43100001ea8: 9b0b7d8b mul x11, x12, x11

44100001eac: 91004129 add x9, x9, #0x10

45100001eb0: 91006108 add x8, x8, #0x18

46100001eb4: eb0a017f cmp x11, x10

47100001eb8: 54fffd08 b.hi 0x100001e58 <_rgb888_to_rgb565_neon_8vals+0x54>

48100001ebc: a8c17bfd ldp x29, x30, [sp], #0x10

49100001ec0: d65f03c0 ret

Processing 16 pixels per iteration (16P)

1void rgb888_to_rgb565_neon_16_vals(Image *src, Image *dst) {

2

3 const uint16x8_t v_4 = vdupq_n_u16(4);

4 const uint16x8_t v_2 = vdupq_n_u16(2);

5 const uint16x8_t v_31 = vdupq_n_u16(31);

6 const uint16x8_t v_63 = vdupq_n_u16(63);

7

8 uint8x16x3_t v_rgb888;

9 uint16x8_t v_rgb565_high;

10 uint16x8_t v_rgb565_low;

11

12 for (int i = 0; i < src->img_width * src->img_height; i += 16) {

13

14 v_rgb888 = vld3q_u8(src->buffer + (i * 3));

15

16 uint16x8_t v_r8_high = vmovl_high_u8(v_rgb888.val[0]);

17 uint16x8_t v_r8_low = vmovl_u8(vget_low_u8(v_rgb888.val[0]));

18

19 uint16x8_t v_g8_high = vmovl_high_u8(v_rgb888.val[1]);

20 uint16x8_t v_g8_low = vmovl_u8(vget_low_u8(v_rgb888.val[1]));

21

22 uint16x8_t v_b8_high = vmovl_high_u8(v_rgb888.val[2]);

23 uint16x8_t v_b8_low = vmovl_u8(vget_low_u8(v_rgb888.val[2]));

24

25 v_r8_high = vaddq_u16(v_r8_high, v_4);

26 v_g8_high = vaddq_u16(v_g8_high, v_2);

27 v_b8_high = vaddq_u16(v_b8_high, v_4);

28

29 v_r8_low = vaddq_u16(v_r8_low, v_4);

30 v_g8_low = vaddq_u16(v_g8_low, v_2);

31 v_b8_low = vaddq_u16(v_b8_low, v_4);

32

33 v_r8_high = vshrq_n_u16(v_r8_high, 3);

34 v_g8_high = vshrq_n_u16(v_g8_high, 2);

35 v_b8_high = vshrq_n_u16(v_b8_high, 3);

36

37 v_r8_low = vshrq_n_u16(v_r8_low, 3);

38 v_g8_low = vshrq_n_u16(v_g8_low, 2);

39 v_b8_low = vshrq_n_u16(v_b8_low, 3);

40

41 v_r8_high = vminq_u16(v_r8_high, v_31);

42 v_g8_high = vminq_u16(v_g8_high, v_63);

43 v_b8_high = vminq_u16(v_b8_high, v_31);

44

45 v_r8_low = vminq_u16(v_r8_low, v_31);

46 v_g8_low = vminq_u16(v_g8_low, v_63);

47 v_b8_low = vminq_u16(v_b8_low, v_31);

48

49 v_r8_high = vshlq_n_u16(v_r8_high, 11);

50 v_g8_high = vshlq_n_u16(v_g8_high, 5);

51

52 v_r8_low = vshlq_n_u16(v_r8_low, 11);

53 v_g8_low = vshlq_n_u16(v_g8_low, 5);

54

55 v_rgb565_high = vorrq_u16(v_r8_high, v_g8_high);

56 v_rgb565_high = vorrq_u16(v_rgb565_high, v_b8_high);

57

58 v_rgb565_low = vorrq_u16(v_r8_low, v_g8_low);

59 v_rgb565_low = vorrq_u16(v_rgb565_low, v_b8_low);

60

61 vst1q_u16((uint16_t *)dst->buffer + i + 8, v_rgb565_high);

62 vst1q_u16((uint16_t *)dst->buffer + i, v_rgb565_low);

63 }

64}

10000000100001ed4 <_rgb888_to_rgb565_neon_16_vals>:

2100001ed4: a9bf7bfd stp x29, x30, [sp, #-0x10]!

3100001ed8: 910003fd mov x29, sp

4100001edc: f9400808 ldr x8, [x0, #0x10]

5100001ee0: f103211f cmp x8, #0xc8

6100001ee4: 54000781 b.ne 0x100001fd4 <_rgb888_to_rgb565_neon_16_vals+0x100>

7100001ee8: f9400c08 ldr x8, [x0, #0x18]

8100001eec: f103211f cmp x8, #0xc8

9100001ef0: 54000741 b.ne 0x100001fd8 <_rgb888_to_rgb565_neon_16_vals+0x104>

10100001ef4: f9400828 ldr x8, [x1, #0x10]

11100001ef8: f103211f cmp x8, #0xc8

12100001efc: 54000701 b.ne 0x100001fdc <_rgb888_to_rgb565_neon_16_vals+0x108>

13100001f00: f9400c28 ldr x8, [x1, #0x18]

14100001f04: f103211f cmp x8, #0xc8

15100001f08: 540006c1 b.ne 0x100001fe0 <_rgb888_to_rgb565_neon_16_vals+0x10c>

16100001f0c: d2800008 mov x8, #0x0 ; =0

17100001f10: d2800009 mov x9, #0x0 ; =0

18100001f14: d280000a mov x10, #0x0 ; =0

19100001f18: 4f008480 movi.8h v0, #0x4

20100001f1c: 4f008441 movi.8h v1, #0x2

21100001f20: 4f0087e2 movi.8h v2, #0x1f

22100001f24: 4f0187e3 movi.8h v3, #0x3f

23100001f28: f940000b ldr x11, [x0]

24100001f2c: 8b08016b add x11, x11, x8

25100001f30: 4c404164 ld3.16b { v4, v5, v6 }, [x11]

26100001f34: 6e241007 uaddw2.8h v7, v0, v4

27100001f38: 6e251030 uaddw2.8h v16, v1, v5

28100001f3c: 6e261011 uaddw2.8h v17, v0, v6

29100001f40: 2e241012 uaddw.8h v18, v0, v4

30100001f44: 2e251033 uaddw.8h v19, v1, v5

31100001f48: 2e261004 uaddw.8h v4, v0, v6

32100001f4c: 6f1d04e5 ushr.8h v5, v7, #0x3

33100001f50: 6f1e0606 ushr.8h v6, v16, #0x2

34100001f54: 6f1d0627 ushr.8h v7, v17, #0x3

35100001f58: 6f1d0650 ushr.8h v16, v18, #0x3

36100001f5c: 6f1e0671 ushr.8h v17, v19, #0x2

37100001f60: 6f1d0484 ushr.8h v4, v4, #0x3

38100001f64: 6e626ca5 umin.8h v5, v5, v2

39100001f68: 6e636cc6 umin.8h v6, v6, v3

40100001f6c: 6e626ce7 umin.8h v7, v7, v2

41100001f70: 6e626e10 umin.8h v16, v16, v2

42100001f74: 6e636e31 umin.8h v17, v17, v3

43100001f78: 6e626c84 umin.8h v4, v4, v2

44100001f7c: 4f1b54a5 shl.8h v5, v5, #0xb

45100001f80: 4f1554c6 shl.8h v6, v6, #0x5

46100001f84: 4f1b5610 shl.8h v16, v16, #0xb

47100001f88: 4f155631 shl.8h v17, v17, #0x5

48100001f8c: 4ea51cc5 orr.16b v5, v6, v5

49100001f90: 4eb01e26 orr.16b v6, v17, v16

50100001f94: 4ea41cc4 orr.16b v4, v6, v4

51100001f98: f940002b ldr x11, [x1]

52100001f9c: 4ea71ca5 orr.16b v5, v5, v7

53100001fa0: 3ca96964 str q4, [x11, x9]

54100001fa4: f940002b ldr x11, [x1]

55100001fa8: 8b09016b add x11, x11, x9

56100001fac: 3d800565 str q5, [x11, #0x10]

57100001fb0: 9100414a add x10, x10, #0x10

58100001fb4: a941300b ldp x11, x12, [x0, #0x10]

59100001fb8: 9b0b7d8b mul x11, x12, x11

60100001fbc: 91008129 add x9, x9, #0x20

61100001fc0: 9100c108 add x8, x8, #0x30

62100001fc4: eb0a017f cmp x11, x10

63100001fc8: 54fffb08 b.hi 0x100001f28 <_rgb888_to_rgb565_neon_16_vals+0x54>

64100001fcc: a8c17bfd ldp x29, x30, [sp], #0x10

65100001fd0: d65f03c0 ret

Optimized version, processing 16 pixels per iteration (using masks)

1void rgb888_to_rgb565_neon(Image *src, Image *dst) {

2

3 const uint8x16_t v_4 = vdupq_n_u8(4);

4 const uint8x16_t v_2 = vdupq_n_u8(2);

5 const uint8x16_t v_255 = vdupq_n_u8(255);

6

7 // expecting 200x200 image

8 assert(src->img_width == TARGET_IMG_WIDTH);

9 assert(src->img_height == TARGET_IMG_HEIGHT);

10 assert(dst->img_width == TARGET_IMG_WIDTH);

11 assert(dst->img_height == TARGET_IMG_HEIGHT);

12

13 uint8x16x3_t v_rgb888;

14 uint16x8_t v_rgb565_high;

15 uint16x8_t v_rgb565_low;

16

17 for (int i = 0; i < src->img_width * src->img_height; i += 16) {

18

19 v_rgb888 = vld3q_u8(src->buffer + (i * 3));

20

21 uint8x16_t v_r = v_rgb888.val[0];

22 uint8x16_t v_g = v_rgb888.val[1];

23 uint8x16_t v_b = v_rgb888.val[2];

24

25 v_r = vaddq_u8(v_r, v_4);

26 v_g = vaddq_u8(v_g, v_2);

27 v_b = vaddq_u8(v_b, v_4);

28

29 // handle overflow

30 uint8x16_t r_mask = vcgtq_u8(v_rgb888.val[0], v_r);

31 uint8x16_t g_mask = vcgtq_u8(v_rgb888.val[1], v_g);

32 uint8x16_t b_mask = vcgtq_u8(v_rgb888.val[2], v_b);

33

34 v_r = vbslq_u8(r_mask, v_255, v_r);

35 v_g = vbslq_u8(g_mask, v_255, v_g);

36 v_b = vbslq_u8(b_mask, v_255, v_b);

37

38 v_r = vshrq_n_u8(v_r, 3);

39 v_g = vshrq_n_u8(v_g, 2);

40 v_b = vshrq_n_u8(v_b, 3);

41

42 uint16x8_t v_r8_high = vmovl_high_u8(v_r);

43 uint16x8_t v_r8_low = vmovl_u8(vget_low_u8(v_r));

44

45 uint16x8_t v_g8_high = vmovl_high_u8(v_g);

46 uint16x8_t v_g8_low = vmovl_u8(vget_low_u8(v_g));

47

48 v_r8_high = vshlq_n_u16(v_r8_high, 11);

49 v_g8_high = vshlq_n_u16(v_g8_high, 5);

50

51 v_r8_low = vshlq_n_u16(v_r8_low, 11);

52 v_g8_low = vshlq_n_u16(v_g8_low, 5);

53

54 v_rgb565_high = vorrq_u16(v_r8_high, v_g8_high);

55 v_rgb565_high = vorrq_u16(v_rgb565_high, vmovl_high_u8(v_b));

56

57 v_rgb565_low = vorrq_u16(v_r8_low, v_g8_low);

58 v_rgb565_low = vorrq_u16(v_rgb565_low, vmovl_u8(vget_low_u8(v_b)));

59

60 vst1q_u16((uint16_t *)dst->buffer + i, v_rgb565_low);

61 vst1q_u16((uint16_t *)dst->buffer + i + 8, v_rgb565_high);

62 }

63}

Optimized version, processing 16 pixels per iteration (saturation add)

1void rgb888_to_rgb565_neon(Image *src, Image *dst) {

2

3 const uint8x16_t v_4 = vdupq_n_u8(4);

4 const uint8x16_t v_2 = vdupq_n_u8(2);

5 const uint8x16_t v_255 = vdupq_n_u8(255);

6

7 // expecting 200x200 image

8 assert(src->img_width == TARGET_IMG_WIDTH);

9 assert(src->img_height == TARGET_IMG_HEIGHT);

10 assert(dst->img_width == TARGET_IMG_WIDTH);

11 assert(dst->img_height == TARGET_IMG_HEIGHT);

12

13 uint8x16x3_t v_rgb888;

14 uint16x8_t v_rgb565_high;

15 uint16x8_t v_rgb565_low;

16

17 for (int i = 0; i < src->img_width * src->img_height; i += 16) {

18

19 v_rgb888 = vld3q_u8(src->buffer + (i * 3));

20

21 uint8x16_t v_r = v_rgb888.val[0];

22 uint8x16_t v_g = v_rgb888.val[1];

23 uint8x16_t v_b = v_rgb888.val[2];

24

25 v_r = vqaddq_u8(v_r, v_4);

26 v_g = vqaddq_u8(v_g, v_2);

27 v_b = vqaddq_u8(v_b, v_4);

28

29 v_r = vshrq_n_u8(v_r, 3);

30 v_g = vshrq_n_u8(v_g, 2);

31 v_b = vshrq_n_u8(v_b, 3);

32

33 uint16x8_t v_r8_high = vmovl_high_u8(v_r);

34 uint16x8_t v_r8_low = vmovl_u8(vget_low_u8(v_r));

35

36 uint16x8_t v_g8_high = vmovl_high_u8(v_g);

37 uint16x8_t v_g8_low = vmovl_u8(vget_low_u8(v_g));

38

39 v_r8_high = vshlq_n_u16(v_r8_high, 11);

40 v_g8_high = vshlq_n_u16(v_g8_high, 5);

41

42 v_r8_low = vshlq_n_u16(v_r8_low, 11);

43 v_g8_low = vshlq_n_u16(v_g8_low, 5);

44

45 v_rgb565_high = vorrq_u16(v_r8_high, v_g8_high);

46 v_rgb565_high = vorrq_u16(v_rgb565_high, vmovl_high_u8(v_b));

47

48 v_rgb565_low = vorrq_u16(v_r8_low, v_g8_low);

49 v_rgb565_low = vorrq_u16(v_rgb565_low, vmovl_u8(vget_low_u8(v_b)));

50

51 vst1q_u16((uint16_t *)dst->buffer + i, v_rgb565_low);

52 vst1q_u16((uint16_t *)dst->buffer + i + 8, v_rgb565_high);

53 }

54}

Scalar Algorithm

1void rgb888_to_rgb565_scalar(Image *src, Image *dst) {

2

3 for (int i = 0; i < src->img_width * src->img_height; i++) {

4 uint8_t r = src->buffer[i * 3 + 0];

5 uint8_t g = src->buffer[i * 3 + 1];

6 uint8_t b = src->buffer[i * 3 + 2];

7

8 // Add half the lost precision before truncating

9 uint16_t r5 = (r + 4) >> 3; // +4 is half of 8 (2^3)

10 uint16_t g6 = (g + 2) >> 2; // +2 is half of 4 (2^2)

11 uint16_t b5 = (b + 4) >> 3; // +4 is half of 8 (2^3)

12

13 // Clamp to prevent overflow

14 if (r5 > 31)

15 r5 = 31;

16 if (g6 > 63)

17 g6 = 63;

18 if (b5 > 31)

19 b5 = 31;

20

21 uint16_t value = (uint16_t)((r5 << 11) | (g6 << 5) | b5);

22

23 ((uint16_t *)dst->buffer)[i] = value;

24 }

25}

Scalar Algorithm (auto vectorized)

10000000100001554 <_rgb888_to_rgb565_scalar>:

2100001554: a9412408 ldp x8, x9, [x0, #0x10]

3100001558: 9b087d28 mul x8, x9, x8

410000155c: b4000988 cbz x8, 0x10000168c <_rgb888_to_rgb565_scalar+0x138>

5100001560: f9400009 ldr x9, [x0]

6100001564: f940002a ldr x10, [x1]

7100001568: f100211f cmp x8, #0x8

810000156c: 54000543 b.lo 0x100001614 <_rgb888_to_rgb565_scalar+0xc0>

9100001570: d37ff90b lsl x11, x8, #1

10100001574: 8b0b014c add x12, x10, x11

11100001578: 8b08012d add x13, x9, x8

1210000157c: 8b0b01ab add x11, x13, x11

13100001580: eb0b015f cmp x10, x11

14100001584: fa4c3122 ccmp x9, x12, #0x2, lo

15100001588: 54000463 b.lo 0x100001614 <_rgb888_to_rgb565_scalar+0xc0>

1610000158c: f100411f cmp x8, #0x10

17100001590: 54000802 b.hs 0x100001690 <_rgb888_to_rgb565_scalar+0x13c>

18100001594: d280000b mov x11, #0x0 ; =0

19100001598: aa0b03ee mov x14, x11

2010000159c: 927df10b and x11, x8, #0xfffffffffffffff8

211000015a0: d37ff9cd lsl x13, x14, #1

221000015a4: 8b0e01ac add x12, x13, x14

231000015a8: 8b0c012c add x12, x9, x12

241000015ac: 8b0d014d add x13, x10, x13

251000015b0: cb0b01ce sub x14, x14, x11

261000015b4: 4f008480 movi.8h v0, #0x4

271000015b8: 4f008441 movi.8h v1, #0x2

281000015bc: 4f0087e2 movi.8h v2, #0x1f

291000015c0: 4f0187e3 movi.8h v3, #0x3f

301000015c4: 0cdf4184 ld3.8b { v4, v5, v6 }, [x12], #24

311000015c8: 2e241007 uaddw.8h v7, v0, v4

321000015cc: 6f1d04e7 ushr.8h v7, v7, #0x3

331000015d0: 2e251030 uaddw.8h v16, v1, v5

341000015d4: 6f1e0610 ushr.8h v16, v16, #0x2

351000015d8: 2e261004 uaddw.8h v4, v0, v6

361000015dc: 6f1d0484 ushr.8h v4, v4, #0x3

371000015e0: 6e626ce5 umin.8h v5, v7, v2

381000015e4: 6e636e06 umin.8h v6, v16, v3

391000015e8: 6e626c84 umin.8h v4, v4, v2

401000015ec: 4f1b54a5 shl.8h v5, v5, #0xb

411000015f0: 4f1554c6 shl.8h v6, v6, #0x5

421000015f4: 4ea51cc5 orr.16b v5, v6, v5

431000015f8: 4ea41ca4 orr.16b v4, v5, v4

441000015fc: 3c8105a4 str q4, [x13], #0x10

45100001600: b10021ce adds x14, x14, #0x8

46100001604: 54fffe01 b.ne 0x1000015c4 <_rgb888_to_rgb565_scalar+0x70>

47100001608: eb0b011f cmp x8, x11

4810000160c: 54000061 b.ne 0x100001618 <_rgb888_to_rgb565_scalar+0xc4>

49100001610: 1400001f b 0x10000168c <_rgb888_to_rgb565_scalar+0x138>

50100001614: d280000b mov x11, #0x0 ; =0

51100001618: d37ff96c lsl x12, x11, #1

5210000161c: 8b0c014a add x10, x10, x12

53100001620: 8b0b018c add x12, x12, x11

54100001624: 8b090189 add x9, x12, x9

55100001628: 91000929 add x9, x9, #0x2

5610000162c: cb0b0108 sub x8, x8, x11

57100001630: 528003eb mov w11, #0x1f ; =31

58100001634: 528007ec mov w12, #0x3f ; =63

59100001638: 385fe12d ldurb w13, [x9, #-0x2]

6010000163c: 385ff12e ldurb w14, [x9, #-0x1]

61100001640: 3840352f ldrb w15, [x9], #0x3

62100001644: 110011ad add w13, w13, #0x4

63100001648: 53037dad lsr w13, w13, #3

6410000164c: 110009ce add w14, w14, #0x2

65100001650: 53027dce lsr w14, w14, #2

66100001654: 110011ef add w15, w15, #0x4

67100001658: 53037def lsr w15, w15, #3

6810000165c: 71007dbf cmp w13, #0x1f

69100001660: 1a8b31ad csel w13, w13, w11, lo

70100001664: 7100fddf cmp w14, #0x3f

71100001668: 1a8c31ce csel w14, w14, w12, lo

7210000166c: 71007dff cmp w15, #0x1f

73100001670: 1a8b31ef csel w15, w15, w11, lo

74100001674: 531b69ce lsl w14, w14, #5

75100001678: 2a0d2dcd orr w13, w14, w13, lsl #11

7610000167c: 2a0f01ad orr w13, w13, w15

77100001680: 7800254d strh w13, [x10], #0x2

78100001684: f1000508 subs x8, x8, #0x1

79100001688: 54fffd81 b.ne 0x100001638 <_rgb888_to_rgb565_scalar+0xe4>

8010000168c: d65f03c0 ret

81100001690: 927ced0b and x11, x8, #0xfffffffffffffff0

82100001694: 4f008480 movi.8h v0, #0x4

83100001698: 4f008441 movi.8h v1, #0x2

8410000169c: 4f0087e2 movi.8h v2, #0x1f

851000016a0: 4f0187e3 movi.8h v3, #0x3f

861000016a4: aa0b03ec mov x12, x11

871000016a8: aa0a03ed mov x13, x10

881000016ac: aa0903ee mov x14, x9

891000016b0: 4cdf41c4 ld3.16b { v4, v5, v6 }, [x14], #48

901000016b4: 6e241007 uaddw2.8h v7, v0, v4

911000016b8: 2e241010 uaddw.8h v16, v0, v4

921000016bc: 6f1d0610 ushr.8h v16, v16, #0x3

931000016c0: 6f1d04e7 ushr.8h v7, v7, #0x3

941000016c4: 6e251031 uaddw2.8h v17, v1, v5

951000016c8: 2e251032 uaddw.8h v18, v1, v5

961000016cc: 6f1e0652 ushr.8h v18, v18, #0x2

971000016d0: 6f1e0631 ushr.8h v17, v17, #0x2

981000016d4: 6e261013 uaddw2.8h v19, v0, v6

991000016d8: 2e261004 uaddw.8h v4, v0, v6

1001000016dc: 6f1d0484 ushr.8h v4, v4, #0x3

1011000016e0: 6f1d0665 ushr.8h v5, v19, #0x3

1021000016e4: 6e626ce6 umin.8h v6, v7, v2

1031000016e8: 6e626e07 umin.8h v7, v16, v2

1041000016ec: 6e636e30 umin.8h v16, v17, v3

1051000016f0: 6e636e51 umin.8h v17, v18, v3

1061000016f4: 6e626ca5 umin.8h v5, v5, v2

1071000016f8: 6e626c84 umin.8h v4, v4, v2

1081000016fc: 4f1b54e7 shl.8h v7, v7, #0xb

109100001700: 4f1b54c6 shl.8h v6, v6, #0xb

110100001704: 4f155631 shl.8h v17, v17, #0x5

111100001708: 4f155610 shl.8h v16, v16, #0x5

11210000170c: 4ea61e06 orr.16b v6, v16, v6

113100001710: 4ea71e27 orr.16b v7, v17, v7

114100001714: 4ea41ce4 orr.16b v4, v7, v4

115100001718: 4ea51cc5 orr.16b v5, v6, v5

11610000171c: ac8115a4 stp q4, q5, [x13], #0x20

117100001720: f100418c subs x12, x12, #0x10

118100001724: 54fffc61 b.ne 0x1000016b0 <_rgb888_to_rgb565_scalar+0x15c>

119100001728: eb0b011f cmp x8, x11

12010000172c: 54fffb00 b.eq 0x10000168c <_rgb888_to_rgb565_scalar+0x138>

121100001730: 371ff348 tbnz w8, #0x3, 0x100001598 <_rgb888_to_rgb565_scalar+0x44>

122100001734: 17ffffb9 b 0x100001618 <_rgb888_to_rgb565_scalar+0xc4>